Still Life Bread Beef Pumpkins Wine Still Life Vermeer

Over the last few blogs about the French artist Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, I have looked at his still-life works which he partly abandoned for financial and artistic reasons around 1733 to concentrate on genre paintings, which once engraved provided him an income from the prints. Chardin never abandoned one genre in order to take up another, but from around 1748 onwards he produced fewer genre scenes and reverted to his beloved still life work of his early career. The number of his genre paintings that he once exhibited regularly dwindled whilst there was an increase in his still life works which were shown at various exhibitions. For many, Chardin will be remembered for his figurative paintings and his portraiture and in this final blog on the artist I will look at some of these works.

One of Chardin's earliest portraits was one which he completed in 1734 and was exhibited at the 1937 Salon with the title A Chemist in His Laboratory. Several years later, in 1744, the painting was engraved by François Bernard Lépicié and given the title Le soufleur, which, according to the seventeenth century, Dictionnaire de l'Académie, is a person using chemistry to search for the philosopher's stone. It is again exhibited at the Salon in 1753 with the title A Philosopher Reading. It is now more commonly known as Portrait of the Painter Joseph Aved. Aved was a good friend of Chardin and had just been elected to the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture. He had assisted Chardin in drawing up the estate inventory of Chardin's first wife, Marguerite Saintard and had been a witness at Chardin's second marriage to Françoise-Marguerite Pouget in 1744. It was one of Chardin's first attempts at portraiture.

In 1737 Chardin completed three paintings which featured young boys, two of which were sons of friends of Chardin. His painting The House of Cards sometimes referred to as The Son of M. Le Noir Amusing Himself by Making a House of Cards featured the son of his friend Jean-Jacques Le Noir, a furniture dealer and cabinet maker and one of Chardin's patrons. He had been a witness at Chardin's second wedding and had bought several of his paintings. The painting shows Le Noir's son enjoying himself making a house of cards. The original work can be found at the National Gallery in London but as with many of Chardin's paintings he painted a number of versions of it. François Bernard, Lépicié created an engraving of the work and added the following caption underneath, which in a way adds a meaning to the depiction:

Dear child all on pleasure

We hold your fragile work in jest

But think on't, which will be more sound

Our adult plans or castles by you built

The Young Draughtsman was also a painting Chardin completed in 1737. It was a subject Chardin had used before. Remember the 1734 painting I highlighted in the previous blog which showed a view from behind of a draughtsman at work, sitting on the floor, face hidden from view. In this painting we clearly see the face of the young man. It is a smooth youthful face which has a look of one lost in the joy of his work. There is a look of pleasure on his face, satisfied with what he has achieved so far. He concentrates on the task ahead as he holds the chalk stick which holds the sharpened chalk. He is relaxed. This scene also gives the viewers of the painting a feeling of relaxation, of serene equanimity and this was a forte of Chardin. Chardin once again has used a subtle set of colours. Milky whites, the black patch of the tricorn hat, the rose colour of the lips and cheek, and various blues for the furnishings and the piece of drawing paper on which the draughtsman has drawn the head of an old man.

Chardin completed another painting of a son of a friend around 1737. It was entitled Portrait of the Son of M. Godefroy, Jeweller, Watching a Top Spin. This work is housed in The Louvre since its purchase from the Godefroy family in 1907. The painting depicts nine-year-old Augustine-Gabriel Godefroy who would later become the controller-general of the French Navy. The young boy smiles and stares at the top as it spins atop of a chiffonier, a low cupboard. The top has been cleared of the quill pen, books and papers which have been pushed to one side to make room for the spinning top. One of the drawers of the chiffonier is partly open in which we can see a chalk holder, similar to the one in the previous work.

Chardin's financial situation had improved since he married his second wife, the wealthy widow, Françoise-Marguerite Pouget in 1744. She brought with her a house in rue Princesse which was close to the house in rue du Four where the Chardin family had lived for many years, although they did not own it. Chardin's new wife also brought to the marriage a sizeable amount of wealth, estimated at in excess of thirty-thousand livres in the form of annuities and cash. Chardin brought about eight thousand livres to the marriage accrued from his share of his first wife's and his mother's estates. Chardin's financial situation was further improved when, in 1752 Chardin was granted a pension of 500 livres by Louis XV. This was the first gratuity Chardin received.

Chardin rarely travelled far from his Left Bank home, just occasionally making the short trips to Versailles and Fontainebleau. In 1757 he finally moved to a new residence as Louis XV had granted him a studio and living quarters in the Louvre, saving Chardin several hundred livres. This apartment, Studio no. 12, which was opposite the church of Saint-Thomas, was vacant following the death of the previous occupant, the goldsmith, François-Joseph Marteau.

Chardin continued to work for the Académie and in 1761 he is given the role of tapissier, the academician tasked with designing the arrangement of the pictures on the walls of the Salon. In Ryan Whyte's 2013 essay Exhibiting Enlightenment: Chardin as tapissier, he commented:

"… Chardin's efforts had merited an observation that he had treated the Salon as both a totality and a collection of parts, recognition that the effect of the Salon arrangement was based on a unified design, Chardin's 'beauty of the whole' and mattered as much as the quality of the individual works therein…"

In a 1763 pamphlet regarding that year's Salon the author commented on Chardin's masterful lay-out of the paintings at the exhibition:

"…One has never arranged the different parts of this collection with more intelligence, as much for the beauty of the whole as for the particular benefit of each of the artworks that make it up…"

In essence the author of the pamphlet suggested that the Salon space was a work of art itself.

In 1763, the Marquis de Marigny, the general Manager of the King's buildings, awarded Chardin 200 livres increase to his pension for taking charge of hanging the exhibits at the Salons. In 1765 he was unanimously elected associate member of the Académie des Sciences, Belles-Lettres et Arts of Rouen, but there is no evidence that he left Paris to accept the honour.

If I was to ask you what paintings by Chardin you have seen or read about, high on that list would be his three pastel self-portraits. Chardin had to turn to pastels around 1771 when he had been taken seriously ill. The cause of his illness was put down to his use of lead-based pigments and binders he used for his oil painting. These had, over time, burnt his eyes and brought on a condition known as amaurosis, a paralysis of the eye leading to deteriorating sight. Coincidentally, Degas suffered from the same ailment and he too had to turn to pastel painting. Chardin's first pastel self-portrait often referred to as Portrait of Chardin wearing Spectacles was exhibited at the 1771 Salon and is now, since 1839, part of The Louvre collection. People were surprised by the exhibit as many believed that Chardin was too ill to paint. They were also surprised by the fact that it was a work of self-portraiture, not a genre he was known for. In 1771, the art correspondent of L'Année litéraire wrote:

"…This is a genre in which no one has seen him work and which, at first attempt, he mastered to the highest degree…"

Denis Diderot, the French philosopher, art critic, and writer praised Chardin and this work, writing:

"…the same confident hand and the same eyes accustomed to seeing nature – seeing nature clearly, and unravelling the magic of its effects…"

The spectacles are delicately perched upon the bridge of his nose. Chardin was forced to wear spectacles due to his failing eyesight and the pair he wears in the painting were made in England. Chardin is depicted in three quarter view. He has turned towards us with his probing brown eyes. How he has depicted himself is symbolic of his trade as an artist. He wears an elaborately entwined blue and white cap, together with a colourful, geometric-patterned scarf which because it has been lit up appears silk-like. The depiction of the artist shows him to be both knowledgeable and astute and the way he has used various tones on the face has made him look almost life-like. Marcel Proust summed up the self-portrait commenting on the ageing artist:

"…Above the outsized pair of glasses that have slipped to the end of his nose and are pinching it between two brand new lenses, are his tired eyes with the dulled pupils; the yes look as if they have seen a lot, laughed a lot, loved a lot, and are saying in tender, boastful fashion: 'Yes, I'm old!' Behind the glimmer of sweetness dulled by age they still sparkle. But the eyelids are worn out, like an ancient clasp, and rimmed with red…"

In 1775 Chardin completed another pastel self-portrait which was exhibited at the 1775 Salon. It was entitled Portrait of Chardin wearing an Eyeshade which is housed at The Louvre. In the painting Chardin has carefully fashioned his costume with the same care he once used when he depicted arrangements of fruit and objects in his still life works. The visor which shades the light from his eyes has an attached dusky pink ribbon. He has a scarf knotted around his head and neck and once again he wears a pair of spectacles. Every detail has been well thought out by Chardin. After seeing the self-portrait in 1904, the then elderly sixty-five-year-old Cezanne wrote about the work to his young friend, the painter and art critic, Emile Bernard:

"…You remember the fine pastel by Chardin, equipped with a pair of spectacles and a visor providing a shade. He's an artful fellow, this painter. Haven't you noticed that by letting a light plane ride across the bridge of the nose the tone values present themselves better to the eye? Verify this fact and tell me if I am wrong…"

The third pastel self-portrait by Chardin, Portrait of Chardin at His Easel was completed in late 1779 but did not enter The Louvre collection until 1966. There are the odd similarities with his 1771 self-portrait in as much as he looks out at us and wears the same turban but in this work, it is decorated with an stylish blue bow. In this work we see Chardin sat in front of his easel, on which is a frame covered with a sheet of blue paper. Our eyes are drawn to his hand, in which he holds a red pastel crayon. His face is half hidden in shadow and it noticeably thinner and his features have taken on a sunken and hollow look, even his eyes have become duller and he looks tired. In his demeanour, we can witness his failing health and in fact this self-portrait was only completed just a few months before Chardin died at 9am on Monday, December 6th 1779, aged 80. He was buried the next day at Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois, at 2 Place du Louvre, Paris.

Chardin had become quite wealthy in his latter years but never quite achieved the great wealth of his contemporaries such as the Rococo painter François Boucher, Nicolas de Largillièrre or the Baroque painter Hyacinthe Rigaud. This is probably due to his moderate output which according to some critics was due to the slowness of his painting which Chardin said was due to his perfectionist attitude to all his works. Other said it was down to his laziness!

I cannot end this look at Chardin's life without telling you about the fate of his family members. As I previously recounted, Chardin's two daughters, one from each of his wives died when they were still very young, but he also had a son from his marriage to his first wife, Marguerite Saintard. Jean-Pierre Chardin was born in November 1731. He too studied to become a painter and in August 1754, won the Académie's first prize for a painting on a historical subject. In 1757 Chardin and his son fell out over Marguerite Saintard's will, Jean-Pierre believing he was not being given what was rightly his. In the September of that year Jean-Pierre received a scholarship from the Académie to study at the French Academy in Rome. On his return to France by sea from Italy Jean-Pierre is kidnapped by English pirates off the coast of Genoa, but later released. In 1767, aged 36, Jean-Pierre travelled to Venice, part of the French Ambassador to Venice's entourage. On July 7th 1772, forty-year-old Jean-Pierre was found drowned in a Venice canal. It is believed that he suffered from severe bouts of depression and committed suicide.

In December 1780, a year after Chardin's death, his second wife Françoise-Marguerite Pouget, left their apartment at The Louvre and moved to her cousin's house in rue du Renard-Saint Sauveur, where she died on May 15th 1781, aged 84.

Chardin was taken seriously ill, both physically and mentally in 1742. It was probable that his temporary decline in health was due to the extreme sadness he suffered due to the passing of his loved ones. Chardin and Marguerite Saintard were married in February 1731. Two months later, his father, Jean Chardin, died. Marguerite Saintard who had given birth to Chardin's son and daughter died in April 1735 and a year later his daughter, Marguerite-Agnès, also died aged three. Chardin was appointed guardian to his son, Jean-Pierre in November 1737. Chardin and his son were now living in a Paris apartment in rue du Four, sub-let to him by his mother. Apart from the deaths of members of his family, the other aspect of his life which probably contributed to his illness was his dire financial situation. He owed his mother for the money she had loaned him after his wife died and he had run up debts with his supplier of painting materials. His financial position worsened even further when his mother, Jeanne-Françoise, died in November 1743.

Chardin needed to improve his financial position. He had already decided to move away from still-life paintings and concentrate on genre works which once made into engravings provide him with much-needed income from the popular prints. Still, money or lack of it, remained a problem for forty-five-year-old Chardin but this was all to change in 1744 when he married his second wife, Françoise-Marguerite Pouget at Saint-Sulpice Church on November 26th 1744. Françoise was the thirty-seven-year-old wealthy widow of Charles de Malnoé and eight years Chardin's junior. Françoise was simply a God-send to Chardin. She saved him from abject poverty and helped him manage his correspondence and his responsibilities on behalf of the Salon, which included arranging the exhibitions and acting as treasurer, from 1755, during which time he was tasked to manage the Académie accounts. Françoise-Marguerite Pouget gave birth to Chardin's daughter, Angélique-Françoise in October 1745 but sadly the baby died in April 1746.

Françoise-Marguerite Chardin appeared in a number of her husband's works, one being The Sertinette or The Bird Organ which he completed in 1751 and was exhibited at that year's Salon as Lady Varying Her Amusements. A serinette was a small barrel organ originally designed for teaching cage birds to sing. The painting is housed at the Louvre which acquired it in 1985. It was the first Royal order passed to Chardin, originally commissioned by Le Normante de Tourneheim, keeper of the King's estates, for Louis XV but two years later, was gifted by the king to the Marquis de Vandières, the brother of Mme de Pompadour, the king's favourite. In the painting we see a lady, modelled by Chardin's wife, Françoise, with the help of a "serinette", teaching the caged bird to sing. The setting for the painting is a bourgeois interior. The woman wears a cap tied under neck and a delicate white scarf-like narrow piece of clothing, worn over her shoulders, similar to a stole and known as a tippet. The tippet she wears partially covers a dress embroidered with flowers. The lady is seated and on her knees is the serinette which she activates by turning the handle. At the left of the painting we see a bird's cage resting on a pedestal. The pedestal has a crossbar which allows one to fix a screen to protect the serin, a small finch-like bird, from the light and from distractions which would hamper it from learning a tune. It was with the help of this salon instrument that the ladies of the "good" society taught their caged birds to sing. In front of the woman, we can see a large work bag which contains her embroidery.

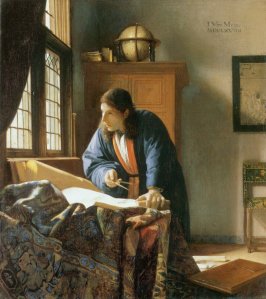

Light streams into the room through the window to the left similar to depictions seen in seventeenth century Dutch paintings – think Vermeer for example, and they obviously had an influence on Chardin.

The Frick Collection, New York

Another version of the painting is in the Frick Collection in New York, which came from the collection of Dominique-Vivant Denon, the director of the Musée Napoléon and bought by the New York gallery in 1926. There is one major difference between the two versions and I will leave you to spot it!

Chardin's 1746 painting Domestic Pleasures also featured his second wife. The painting was commissioned by Lvise Ulrike, the sister of Frederick the Great of Russia and the wife of Adolf Frederick the Crown Prince of Sweden and the country's future king. However, the commissioning was far from straight forward. Lvise Ulrike was a great fan of Chardin's paintings and wanted him to paint two works and she gave him the titles of them to be The Strict Upbringing and The Gentle, Subtle Upbringing. Unfortunately for her, Chardin was a slow painter which in a letter dated October 1746, he stated:

"…I take my time because I have developed the habit of not leaving my paintings until, to my eyes, there is nothing more to add…"

Chardin's assertion that it was diligence and being a perfectionist were the reasons for the long time he took on each painting was challenged by others who put it down to his laziness. The princess was however not amused by this slow pace. Bizarrely Chardin finished the two paintings in 1746 but the subjects had nothing to do with the titles supplied by the princess. They appeared at the 1746 Salon entitled Domestic Pleasures and The Housekeeper and were subsequently given to Lvisa via the Swedish ambassador in Paris in February 1747.

My last offering of a Chardin painting, featuring his wife, Françoise-Marguerite Pouget, is his pastel work entitled Portrait of Madame Chardin, née Françoise-Marguerite Pouget which he completed in 1775 when he was seventy-six and which can now be seen in the Louvre. A year later he repeated the portrait, which is now housed in the Art Institute of Chicago. Before us we see the face of Chardin's second wife, sixty-eight-year-old Marguerite Pouget. Her face is wrapped to the eyes in an almost nun-like headdress, a head covering which often featured in Chardin's paintings. Her forehead has an ivory pallor. Look how a shadow is cast by the headdress and the daylight on her temple is filtered through its linen material. Her mouth is closed tightly and she is not smiling. Her gaze is frosty. There is a dullness about her eyes. We detect wrinkles around her eyes. Chardin has managed to create all the indicators of old age. Chardin's use of colours is masterful. The whiteness of her face is achieved with pure yellow and the pallid face has no white in it at all. The pure white cap is made solely of blue. The art critics loved the portrait. The eighteenth-century writers, publishers, literary and art critics, the brothers Edmond, and Jules de Goncourt wrote:

"…it is in the portrait of his wife that he reveals all his ardour, his vitality, the strength and energy of his inspired execution. Never did the artist's hand display more genus, more boldness, more felicity, more brilliance than in this pastel. With what a vigorous, dense touch, with what freedom and confidence he wields his crayon; liberated from the hatching that previously damped his voice or obscured his shadows. Chardin attacks the paper, scratches it, presses his chalk home……To have represented everything in its true colour without using the real shade, this is the tour de force, the miracle that the colourist has achieved…"

Chardin produced many genre paintings in the late 1730's and early 1740's which depicted female servants carrying out their household duties. There are three versions of The Turnip Peeler which he completed around 1738. One is housed in the National Gallery of Art in Washington whilst one can be found in the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen in Munich. The third version was previously in Berlin, acquired for Frederick II of Prussia but which is now lost. The Washington version was exhibited at the 1739 Salon by Chardin and bought around that time by the Austrian ambassador, Prince Joseph Wenzel of Liechenstein. It became part of the Washington National Gallery collection in 1952. Before us we see a large woman sitting slightly hunched on a chair, knife in hand, about to peel a turnip. She gazes out blankly, lost in thought. She is surrounded by other vegetables such as a large pumpkin, some cucumbers and a bowl of water which contains the previously scraped turnips. In front of her we see a copper cauldron and a saucepan which is leaning against a bloodstained butcher's block, in which a meat clever has been driven. This genre piece by Chardin is not one which has an anecdotal element to it, neither has it any social comment about the plight of servants.

A painting which has connections with The Turnip Peeler is The Return from Market. Once again, three versions of this painting exist. One, dated 1738, is in Ottawa's National Gallery of Canada, and was presented to the Salon in 1739. One is at Schloss Charlottenburg in Berlin and is dated 1738, and the third is housed in The Louvre. It is believed that the version held in Berlin was a companion piece to The Turnip Peeler, with the two being acquired by Frederick the Great in 1746. This painting unlike its companion piece still survives, but only just, as it was found in the park at Charlottenburg after the Schloss was pillaged by Austrian troops in 1760. Since that time this work by Chardin has never left Berlin. An engraving by François-Bernard Lépicié was made from the Louvre version. Lépicié made engravings of a number of Chardin's paintings and prints from the engravings were a great source of income for the artist. When the painting was exhibited at the 1739 Salon it received great critical acclaim. The French literary brothers, Edmond de Goncourt and Jules de Goncourt, wrote about the work stating:

"…the colours placed side by side give the painting the appearance of a tapestry in gros point…"

While the writer Henri de Chennevières was even more enthusiastic when he wrote about Chardin's use of colour:

"…the milky whites of the woman's skirt, the unique faded blues of the apron….., the floury, golden crust on the loaves of bread. And the two bottles on the floor, the red seal on one of them echoing the ribbon on her sleeve…"

My final two paintings by Chardin in this blog are his small pendant works, (49 x 39cms), The Diligent Mother and Saying Grace, both of which were completed in 1740. Chardin gave both works to Louis XV in the November following their showing at the Salon and are now housed at The Louvre. The Diligent Mother was the less famous of the two works and depicts a young mother, wearing pink slippers and blue stockings, her scissors hanging at her waist as she and her daughter inspect a piece of embroidery. In the foreground, by her, we see a wool winder and skein with coloured balls of wool inside the base of it. A bobbin can be seen lying on the floor as well as a box which acts as a pin cushion, next to which is curled-up pug. To the extreme right we see a red fire screen, while behind the mother stands a large green folding screen which prevents the light from the half-open door entering the room. The work was considered to be a genre piece in which a well-to-do middle-class mother shows the daughter a mistake she has made in her tapestry. One other interesting fact about this work was when an engraving was made of it by the engraver François-Bernard Lépicié, he added lines of moralistic verse to it so as to explain what was depicted:

"…A trifle distracts you my girl

Yesterday this foliage was done

See from each stitch you have made

How distracted your mind is from work

Believe me, avoid laziness

Remember this one simple truth

That hard work and wisdom together

Are more valued than beauty and wealth…"

Were these salutary words approved by Chardin? Are they Chardin's or Lépicié's words?

The final Chardin painting for today's blog is entitled Saying Grace and is one of his most celebrated and most popular of his works. The theme of the painting is prayer before meals and was one of the most famous works by Chardin but when it was shown at the 1740 Salon it received very little praise. However, along with its pendant piece, The Diligent Mother, it was given to Louis XV. It remained in the royal collections until the French Revolution; it then entered the Muséum Central des Arts, which would later become the Louvre, in 1793. It was largely forgotten until the nineteenth century when Chardin was "rediscovered". It was then that the work was hailed as being emblematic of a morally upright, industrious social class and was often contrasted to the debauched, wasteful lifestyle of the aristocracy. Chardin in this tender work depicting a mother teaching her children to pray highlights commendable and hidden qualities and like many of his genre works, once again depicts the satisfied life which comes from a sense of duty, unlike the Rococo painters of the time, such as François Boucher, who depicted the dalliance and flirting of the nobility and upper-classes at their garden luncheons, and moonlit promenades.

In my final blog about Chardin I will be looking at his latter days and his works of portraiture.

During the last years of the 1720's and the early part of the 1730's Chardin completed many paintings which were termed as retours de chasse, literally meaning returns from the hunt, paintings which depicted the animals killed by hunters and the instruments used for the kill. Although such sights of dead animals may not be popular during our time now, they were very sought after during Chardin's time and during the seventeenth century in the Netherlands.

One such painting is his work Still Life with Hare which he completed around 1730 and can be found in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The first interesting thing to note about this painting is that there is no geometrical demarcation of the background wall and the surface on which the hare lies. Neither the wall nor the surface are marked in any way other than the shadow cast by the paws and body of the dead animal. The depiction is all about the dead animal and the items used to kill it and bring it home. It is some ways a minimalistic depiction which simply depicts the hare lying on top of a game bag next to a powder flask tied with a dark blue ribbon, both of which were his own props and appear in other works. Once again take time to examine the animal and the number of shades of brown Chardin has used in its depiction.

Two other Chardin's retours de chasse works are thought to be pendant pieces which he completed in 1728. In the painting, Two Rabbits with Game Bag, Powder Flask and Orange, our eyes immediately focus on the Seville orange in the left foreground which is illuminated by a shaft of light emanating from the left. Once our focus leaves the orange it moves upwards towards the two dead wild rabbits, the powder flask and the game bag which are painted with a mixture of dirty whites, grey, cream, and beige and highlighted in blue. On the stone surface we glimpse at a few wisps of straw.

The pendant piece is Partridge, Bowl of Plums and Basket of Pears. The grey partridge is depicted secured by a large nail to the wall in front of a stone alcove. On a stone ledge in the middle and foreground we can see a plethora of fruit and vegetables all of which have been meticulously painted. There is a large basket of pears, a bowl of plums, two peaches, one of which has had a chunk removed, two figs, some blackberries and some sticks of celery all of which are placed on two levels. The colour palette used is a mass of sumptuous colours and tones and is much richer than its companion piece. Again, in this work the light source is to the left of the depiction which links the two pictures. Like its companion painting, it is one you need to study carefully and take in the colours, shapes and shadows Chardin has given to the work. Both paintings are part of the Staatliche Kunsthalle in Karlsruhe, Germany.

Around 1733 Chardin changed his painting style from works of still-life which depicted inanimate objects to genre painting. Why did Chardin change his style? Maybe the reason was given by comments made by Pierre-Jean Mariette, a collector of and dealer in old master prints, a renowned connoisseur, especially of prints and drawings, and a chronicler of the careers of French, Italian and Flemish artists. He tells the tale of Chardin being at his friend's house, the French Rococo painter, Joseph Aved, when a lady called. Mariette continues with the story:

"…One day a lady came to find M. Aved to request him to do her likeness; she wanted it to extend as far as her knees and claimed that she could afford to pay only four hundred livres. She left without a deal being struck for, although M. Aved was not as busy as he has been since, her offer seemed to him to be far too modest. M. Chardin, on the contrary, urged him not to waste the opportunity and tried to demonstrate that four hundred livres was a reasonable payment for someone who was not yet very well known. 'Yes' said Aved, 'if a portrait was as easy to do as a saveloy.' He said this because M. Chardin was engaged in painting a picture for a fire screen in which he was depicting a saveloy on a dish. Aved's remark made a strong impression on Chardin; he took it as the truth rather than jest and began seriously to re-examine his career…"

Chardin's thought process made him realise that the public would soon tire of his inanimate still-life and his retours de chasse works. He was also wise enough to understand that to turn his attention to painting live animals he would put himself up against the leaders in that field, François Desportes and Jean-Baptiste Oudry and he would struggle to compete and sell such works. His decision to change genres was two-fold. Firstly, there was the financial aspect as he knew that there would be plentiful profit from prints made from his genre scenes whereas nobody ever made prints of still-life works. Secondly, there was the artistic argument for him to change genre. His still-life works were classed by the French Academy as the lowest in the hierarchy of artistic genres whereas the status of genre scenes which included human figures was much higher in the hierarchy and portraiture which Chardin started to do in 1734 was even higher up in the artistic pecking order. Maybe part of the reason could have been that Chardin no longer felt fulfilled with his still life works.

One of Chardin's most famous works was a small work (21 x 17cms) in the style of Dutch cabinet paintings entitled Young Student Drawing, often referred to as The Draughtsman. The work is housed in the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas. Chardin returned to the composition repeatedly over a twenty-year period, and completed no fewer than twelve versions, which illustrates how important the subject was to him. We see a young draughtsman from behind. He is seated on the ground with his legs wide apart, wearing a tricorn hat. He is copying in red chalk the figure of a male nude which is pinned to the wall in front of him. Again, look at the details of the work. The boy's overcoat is torn on the left shoulder and through the hole we glimpse the red of his suit. Our eyes are immediately drawn to this spot of red. On the floor we can see a knife which the young man has used to sharpen his pencils and leaning against the wall to the right we can see a stretcher and a bare canvas. Through this work, Chardin seems to have been making a comment on the arduous process of artistic training followed by the French Academy. Chardin used to copy his teacher's academic studies just as the young man in the painting is doing. Chardin recalled his early training with Pierre-Jacques Cazes when he was a young boy:

"…We were set at the age of seven or eight with pencil holder in hand……We spent long hours bent over our portfolio…..We spent five or six years drawing from the model…..The eye has to be taught to look at nature…"

In 1733 Chardin completed his genre work entitled Woman Sealing a Letter which is housed at Schloss Charlottenburg in Berlin. It is a large painting (146 x 147cms) and was the largest work Chardin had attempted. Was this choice of size a way of Chardin showing the public what he was capable of producing? Engravings were made of this painting in 1738 and it was the earliest engraving made of a painting by Chardin. The lady holds her letter which she has just written in one hand whilst the other holds sealing wax and she awaits impatiently for her servant to light the candle which will in turn melt the wax and seal the letter. Our eyes are immediately drawn to the white envelope and the red sealing wax. Women and letter writing were a popular motif in the seventeenth century Netherlandish paintings and maybe Chardin had seen some examples. The painting depicts an affluent woman in a wealthy setting but soon Chardin veered towards portraying more modest folk in their domestic settings. This painting was exhibited at the Place Dauphine, Paris in 1734 and at the Salon in 1738.

Prime examples of Chardin genre paintings depicting a poor household are his 1733 work entitled The Washerwoman and Woman Drawing Water at the Cistern both of which are housed at the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm. These two paintings have been classified of works of Intimism, a French term which is applied to paintings and drawings of quiet domestic scenes. The Washerwoman which Chardin completed in 1733 was one of sixteen paintings by him which were exhibited in June 1734, at the Exposition de la Jeunesse in place Dauphine in the French capital.

The Washerwoman when first exhibited was, because of its beautiful rendering of the contrast of the colours and textures, billed as a work in the style of the Flemish 17th-century artist David Teniers the Younger. It was later exhibited at the 1737 Paris Salon, where some critics even likened his style to that of Rembrandt. Chardin was undoubtedly inspired by Rembrandt's honest descriptions of household chores. In the work we see a servant engaged in the servile, domestic chores of the household. The woman is depicted scrubbing the washing in a large wooden wash bucket. Chardin has portrayed her in full-face albeit gazing away from her work. She seems preoccupied almost as if something has distracted her attention, or maybe she has been depicted in an instant of idle daydreaming.

The other work classed as one of a pair with The Washerwoman was his painting Woman Drawing Water at the Cistern. Here we see everyday chores in a kitchen far away from the rooms occupied by the master and mistress. We see a female servant, who because of her pose and the large bonnet she is wearing, has her face hidden from view. She is bent over filling a jug from a large copper urn. To the left of the urn we can see a side of meat hanging from a hook. Behind her there is a doorway through which we can see another servant clasping the hand of a small child. Once again, several of the objects depicted came from Chardin's home, such as the copper cistern.

The beautiful rendering of the contrast of the colours and textures has been compared with works by Flemish masters such as David Teniers the Younger.

Carl Gustaf Tessin, one of the most brilliant personages of his day, and the most prominent representative of French culture in Sweden was tasked by the Swedish Court to purchase the two works on behalf of Crown Prince Adolf Fredrik and his future wife, Lovisa Ulrika at a Paris auction in 1745.

..…….. to be continued.

Chardin's road towards married life was a protracted one. The love of his life was Marguerite Saintard, the daughter of Simon-Louis Saintard, a Parisian tradesman and his wife Françoise Pantouflet and in 1723 a contract of marriage was agreed with financial details and dowries having been accepted by both parties and the future in-laws. However, Marguerite's parents were wary with regards how Chardin would support their daughter and needed Chardin's position to be "consolidated" before any marriage could take place. One has to remember that it was not until 1728 that Chardin was accepted into the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture which meant he had a greater chance of selling his work. However, in 1730 he had acquired his first patron, Comte Conrad-Alexandre de Rothenbourg, Louis XV's ambassador to Madrid, who was buying up many of his paintings.

In 1731 Chardin was commissioned by Rothenbourg to paint two still-life canvases for his library on Rue du Regard, in Paris. It was decided that they should be painted and then hung high up on either side of the door to the room, as they were initially designed to be viewed from below. One was entitled Attributes of the Arts which is housed in St Petersberg's Institute of Russian Literature

The other was Attributes of the Sciences. It is interesting to note that two of the items depicted in this latter work belonged to Chardin. They were two large Turkish carpets which normally covered the oak tables in Chardin's study. In the painting we can see a graphic characterisation of the Scientific Revolution and the discoveries and inventions from that time. We see instruments that were connected with observation such as a telescope, and a microscope. There were objects which harked back to times of discovery and knowledge such as the globe, as well as books and maps. These items also symbolise the documentation and spreading of knowledge in science. This still-life work focuses on inanimate objects that represent the theme and motif of the image. The depiction is without people and the scientific instruments are placed in the centre of the painting and reflect the scientific revolution and the new world view and perspective that was gradually accepted during the artist's time.

Chardin and Marguerite, signed a second marriage contract in January 1731. It is ironic that the delay to the marriage was due to Marguerite's parents concern about Chardin's ability to financially provide for their daughter and yet her dowry as stated in the second contract (1000 livres) was less than that stated in the first marriage contract (3000 livres) eight years earlier. The probable reason for this reduction was that since the signing of the first contract both of Marguerite's parents had died. Chardin and Marguerite married on February 1st 1731 at the nearby church of Saint-Sulpice.

In Chardin's 1735 painting A Lady Taking Tea, it is believed that his wife, Marguerite Saintard, was the model for the depiction. It is a beautiful and, in some way, a haunting image of a lady drinking tea, because the work was completed just two months before she died.

In 1728 Chardin produced two more still-life works featuring cats. One was entitled Cat with Salmon, Two Mackerel, Pestle and Mortar which is now housed in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid. In this work we see the cat with its tail erect placing its paw tentatively on a piece of salmon. Under the salmon fillet we can just make out a dark green pottery lid, next to which is a leek and an onion and on the far right there is a pestle and mortar.

The other work, entitled Cat with Ray, Oysters, Pitcher and Loaf of Bread is also housed in the Madrid museum and features Chardin's well-known ray. Like the previous painting this work depicts a nervous tortoiseshell cat as it hesitantly places its paws on the oysters. The depiction is completed by the ray. This is complimented by the inanimate objects – the green glazed earthenware dish, a small jug and part of a loaf of bread. Chardin's still life works are arranged with objects that belonged to him and which he repeatedly used in his compositions. These two paintings were in the collection of Baron Edmond de Rothschild and were acquired for the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection in 1986. Both reflect the influence of Dutch painting that is evident in the artist's early work, in which he adapted northern subjects and formats to his own manner. Chardin had now begun to supplement his inanimate objects with living animals that in some way interpose the calmness of the depiction. The composition of these two paintings is pure simplicity with the arrangement of the cats and the inanimate kitchen items on a stone ledge. Chardin's rich colouring creates a visually believable image.

Another of Chardin's early still-life paintings housed in the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection in Madrid is Still Life with Pestle and Mortar, Pitcher and Copper Cauldron, which he completed around 1732. In this work, Chardin depicts a wooden pestle and mortar, a pottery pitcher, a small copper cauldron or cooking pot and a fired terracotta dish of a type used for cooking. The foreground is dominated by a white cloth of a thick weave, atop of which we see an arrangement made up of onions, potatoes, two eggs and some thin leeks. Colour played a big part in the success of Chardin's works and this painting is a fine example of Chardin's use of colour and tones. Look, for example, at the whites in the foreground. Chardin has used various shades of white to depict the skin of the onions, the eggs and the coarse tablecloth to give a feel for the texture of the objects. The wooden pestle and mortar on the left can be seen in other paintings by Chardin, as would the pitcher and the copper cooking pot.

Chardin uses ploys which can also be seen in Flemish and Dutch still-life paintings to create a sense of depth by depicting the white cloth fallings over the front of the table top. The end of the leek also appears to overshoot the table top to give a 3-D impression and this reminds one of the similar trompe l'oeil technique when objects overlap tables in many Netherlandish paintings, such as in the Still Life painting by the Flemish painter Jan Davidsz. de Heem in which we see the claws of a lobster and the curled peel of a lemon overhang the green velvet table covering.

In 1930 Chardin completed his painting, Bowl of Plums, a Peach and Water Pitcher, which is now housed at The Phillips Collection in Washington DC. The bowl of plums we see in this work was a favourite of Chardin's and appeared in some of his other works. What is unique about this painting is his inclusion of the white water pitcher with its exquisite butterfly pattern and delicate silver mount. It puzzled art historians as to whether this item was a figment of the artist's imagination but it is known that Chardin needed to have the objects in front of him when copying them and so it is thought that he had acquired this Chinese vessel at some time. Chardin has gone for a scumbled (the application of a very thin coat of opaque paint to give a softer or duller effect) background, so not to detract from the pitcher and fruit.

The next six years were a rollercoaster of personal events for Chardin. His father, Jean-Pierre died at the beginning of April 1731 but Chardin received very little from his father's estate due to the fact he was the product of his father's second marriage and there were many "calls" on the estate from his father's ex-wife and their children of his first marriage. In the end Chardin inherited 1,711 livres. On November 15th 1731, Chardin's son, Jean-Pierre was born and two years later, in 1733, his daughter, Marguerite-Agnès, was born. A period of sadness was to soon follow with Chardin's wife Marguerite dying on April 13th 1735 at the young age of 22 and his daughter dying in 1737, aged just four. These deaths probably took their toll on Chardin as in 1742 he became very ill and takes no part in that year's Salon.

..……to be continued

One of the many blogs I follow is one entitled Victorian Paris Blog and the author is Iva Polansky. I was pleased to read that she has turned the various blogs into an e-book. Take a look at it:

https://victorianparis.wordpress.com/2019/04/10/victorian-paris-blog-is-a-book/

In my last few blogs I have concentrated on lesser-known artists but for the next few blogs I will be delving into the life and works of one of the greatest French artists of the eighteenth century. This painter is rightly regarded as one of greatest masters of Still Life in the history of art. I give you Jean Baptiste Siméon Chardin. Chardin who was born in 1699 and grew up in a time when the painting style of the establishment was Rococo; an affected style which was overflowing with allegorical images from classical mythology depicted amongst a whirl of lavish adornments. Chardin would not follow that theatrical trend, much preferring his works to be rational conversation pieces. His works of art were ones of truth, self-effacement, and tranquillity.

Jean Baptiste Siméon Chardin was born on the Parisian Left Bank quarter of Saint-Germain-des-Prés on November 2nd 1699. His father was Jean Chardin, a master cabinet-maker, and his mother was Jeanne-Françoise David, his father's second wife. The family lived in a house on the rue de Seine, close to the church of Saint-Sulpice, which has, along with its "Rose Line", gained notoriety because of the film The Da Vinci Code. Jean Baptiste Siméon Chardin was baptised the next day in the church with fellow cabinet maker Siméon Simonet and the wife of another cabinet maker, Anne Bourgine acting as godparents.

From an early age Chardin found joy in drawing and painting and his father decided to nurture his son's love affair with painting. He had his son join the Académie de Saint-Luc and by securing him a position at the studio of the French historical painter, Pierre-Jacques Cazes to teach his son the finer techniques of painting. It was whilst studying at Cazes' studio that Chardin learned to draw and studied the history of painting. This was the same sort of tuition young artists were taught at the Académie Royale de Peinture. However, entry to such a prestigious establishment was not open to all and Chardin never studied there but managed, through Cazes, to acquire similar training. During his time with Cazes Chardin set his mind to become a history painter but that was to change. Why did he change? The answer was probably quite fundamental – he was not a very good history painter and so he decided to set upon a different artistic journey.

One of his earliest paintings was The Game of Billiards which he completed in 1725. It is a painting which depicts a large number of people in a real-life setting. This work by Chardin which is housed in Musée Carnavalet in Paris was probably a reference to his father who made billiard tables for a living. During those early days he turned his attention to genre scenes but soon found that his greatest satisfaction came from depicting animals involved in game hunting which were known as tableaux de chasse, (hunting pictures). He believed that such paintings should be as realistic and unique as possible, once stating:

"…I must forget everything I have seen, and I must even forget the way such objects by others…"

Chardin exhibited his first still life painting on September 25th 1728. The date was important as this was the date, he was accepted by the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture. Charles-Nicolas Cochin, the Younger, the French art critic tells the story of Chardin and that fateful day:

"…Encouraged by the praise he was receiving from a number of artists, he decided in 1728 to present himself to the Académie. He was eager to know what the leading officers of this august body thought. He employed a little ruse – a perfectly legitimate one – to be sure of winning their approval. He placed the paintings he was going to present in the first room, as if by chance, and waited in the second room. M. de Largillierre, an excellent painter, one of the best colourists and a knowledgeable theorist on the effects of light, came to find him. He stopped and studied the paintings before coming in to the room where M. Chardin was waiting. As he entered, he said: 'You have got some very fine paintings there. They must be by a skilled Flemish painter. Flanders is an excellent school of learning about colour. Let us see your paintings now'. 'Monsieur, you have just seen them' said M. Chardin 'What? Those paintings which….?' 'Yes, Monsieur.' 'Oh, my friend, said M. de Largillierre, embracing him, present yourself without hesitation…"

However, before this acceptance, Louis de Boullongne, the first painter to the king, and who had served as one of its highest-ranking officials of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, entered the room. Chardin grasped the opportunity to ingratiate himself with Louis de Boullongne, informing him that ten or twelve of the paintings in the first room were painted by him but added that if the Académie found any to their liking they could have them! M. de Boullongne dryly commented that Chardin was already talking about being enrolled when he had yet to be accepted but said he was pleased that Chardin had drawn his attention to the paintings. Cochin goes on to say that Jean Baptiste Siméon Chardin was accepted by the Académie to general applause and the institution accepted two of Chardin's paintings as his morceaux de reception (reception pieces). Chardin was accepted into the Académie but as a painter "specialising in animals and fruit" which, according to the Académie at the time, was the most inferior genre of all.

One of the Chardin's paintings accepted by the Académie was entitled The Ray, which he completed in 1726. The painting remained in the collections of the Academy, before entering, during the French Revolution in 1793, the Muséum Central des Arts, which would later become the Louvre. It is without doubt one of his early masterpieces and it has remained on public display without interruption since 1728. The French novelist, Marcel Proust, on seeing the painting described the fish as:

"…the beauty of its vast and delicate structure, tinted with red blood, blue nerves and white muscles, like the nave of a polychromatic cathedral…"

It is a depiction of contrasts. The central and dominant figure in the painting is the gutted and skinned ray, a repulsive blood-stained fish with almost a human face. To the right we see a collection of everyday inanimate objects, a skimming ladle, the casserole, knife and the pitcher whilst to the left of the hanging fish we have items from the vegetable and animal world. We see oysters, a carp and the strange figure of a young cat, fur raised in fright at something it has seen outside the painting. Cats would often feature in Chardin's paintings. The depiction of the skinned ray itself with its expressionless and eerie gaze is spellbinding.

Chardin's second morceau de reception for the Académie was his painting entitled The Buffet. This work was completed in 1728 some two years after the completion of The Ray. In the foreground we see a hunting dog, standing next to a wine cooler and a bunch of radishes. He is staring up at a dark grey parrot which is perched on the handle of a large ewer. The dog is obviously distressed at the sight of the bird leaning towards the fruit. To the left on the end of the curved sideboard there is a pewter jug, two stemmed glasses of wine, one of which is tilting over possibly due to the dog pulling the white linen table cloth. At the other end of the sideboard there are two carafes which have been described as being made of very fine fern ash glass, two bowls without handles, probably Chinese in origin. The focus of our attention is the central high pyramid stack of plums and peaches which sits on a crumpled white tablecloth. Below the fruit is a plate of oysters and two golden rounds of lemon. Again, as we have seen in many Flemish still-life works, Chardin has displayed his artistic talent by his depiction of the folds in the tablecloth, the curling lemon peel and the three-dimensional look of the silver tray and knife which overlap the edge of the sideboard. Again Marcel Proust lovingly commented on what he saw:

"…Clear as daylight, enticing as spring water, glasses in which a few mouthfuls of sweet wine linger as in the throat, stand beside glasses that are already almost empty, like symbols of thirst assuaged. Bent over like a wilted bloom, one glass is half toppled; this happy stance shows off the shape of its foot, the delicacy of its joints, the transparency of the glass, the elegant flare of its cup…"

Many of the items depicted in those still life paintings emanated from other works by Chardin. Take a look at his painting entitled Pewter Jug with Basket of Peaches, Plums and Walnuts, which he completed the same year and is part of the Staatliche Kunsthalle collection of Karlsruhe, and one can recognise the pewter jug which is part of The Buffet depiction.

Also in his painting Carafe of Water, Silver Goblet, Peeled Lemon, Apple and Pears which he completed in 1728, and also part of the Staatliche Kunsthalle collection of Karlsruhe, we also see items which appeared in The Buffet which makes one wonder whether these two paintings were preliminary studies for the larger work.

Chardin chooses his objects and fruit carefully, for their shape and for their colour. Look at the variety of colours. They are all arranged carefully with the contrast between the soft pink of the peaches and the velvety blue of the plums, the carmine red of the apple and the acid green of the pear or the sharp yellow of the lemon.. It is magical to see how he alternates between hot and cold colours and how he juxstaposes the various shapes of the fruits and the rectilinear surface they are placed on.

..….. to be continued.

williamsshave1981.blogspot.com

Source: https://mydailyartdisplay.uk/tag/jean-baptiste-simeon-chardin/

0 Response to "Still Life Bread Beef Pumpkins Wine Still Life Vermeer"

Post a Comment