Popul Vohsomeone Has Once Again Began to Play Over Our Heads

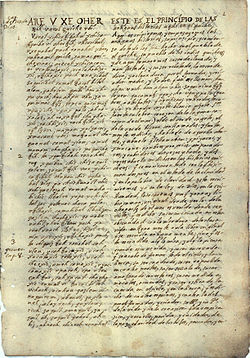

The oldest surviving written account of Popol Vuh (ms c. 1701 past Francisco Ximénez, O.P.)

Popol Vuh (also Popol Wuj or Popul Vuh or Pop Vuj )[i] [2] is a text recounting the mythology and history of the Kʼicheʼ people, one of the Maya peoples, who inhabit Guatemala and the Mexican states of Chiapas, Campeche, Yucatan and Quintana Roo, besides as areas of Belize and Honduras.

The Popol Vuh is a foundational sacred narrative of the Kʼicheʼ people from long before the Spanish conquest of Mexico.[3] It includes the Mayan creation myth, the exploits of the Hero Twins Hunahpú and Xbalanqué,[4] and a chronicle of the Kʼicheʼ people.

The name "Popol Vuh" translates as "Volume of the Community", "Book of Counsel", or more literally as "Book of the People".[5] It was originally preserved through oral tradition[6] until approximately 1550, when it was recorded in writing.[7] The documentation of the Popol Vuh is credited to the 18th-century Spanish Dominican friar Francisco Ximénez, who prepared a manuscript with a transcription in Kʼicheʼ and parallel columns with translations into Castilian.[6] [8]

Like the Chilam Balam and similar texts, the Popol Vuh is of particular importance given the scarcity of early accounts dealing with Mesoamerican mythologies. After the Castilian conquest, missionaries and colonists destroyed many documents.[9]

History [edit]

Father Ximénez's manuscript [edit]

In 1701, Male parent Ximénez came to Santo Tomás Chichicastenango (besides known as Santo Tomás Chuilá). This town was in the Quiché territory and is likely where Father Ximénez start recorded the work.[10] Ximénez transcribed and translated the account, setting up parallel Kʼicheʼ and Spanish language columns in his manuscript (he represented the Kʼicheʼ language phonetically with Latin and Parra characters). In or effectually 1714, Ximénez incorporated the Castilian content in book one, chapters 2–21 of his Historia de la provincia de San Vicente de Chiapa y Guatemala de la orden de predicadores. Ximénez'southward manuscripts were held posthumously by the Dominican Order until General Francisco Morazán expelled the clerics from Guatemala in 1829–30. At that time the Social club'southward documents were taken over largely by the Universidad de San Carlos.

From 1852 to 1855, Moritz Wagner and Carl Scherzer traveled in Central America, arriving in Guatemala Urban center in early May 1854.[11] Scherzer found Ximénez'south writings in the university library, noting that at that place was one particular particular "del mayor interés" ('of the greatest interest'). With assistance from the Guatemalan historian and archivist Juan Gavarrete, Scherzer copied (or had a copy made of) the Castilian content from the last one-half of the manuscript, which he published upon his return to Europe.[12] In 1855, French Abbot Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg also came across Ximénez'due south manuscript in the academy library. However, whereas Scherzer copied the manuscript, Brasseur apparently stole the university'southward volume and took it back to France.[13] After Brasseur's death in 1874, the Mexico-Guatémalienne collection containing Popol Vuh passed to Alphonse Pinart, through whom it was sold to Edward East. Ayer. In 1897, Ayer decided to donate his 17,000 pieces to The Newberry Library in Chicago, a projection that was non completed until 1911. Father Ximénez's transcription-translation of Popol Vuh was among Ayer'south donated items.

Father Ximénez's manuscript sank into obscurity until Adrián Recinos rediscovered it at the Newberry in 1941. Recinos is generally credited with finding the manuscript and publishing the starting time straight edition since Scherzer. But Munro Edmonson and Carlos López attribute the showtime rediscovery to Walter Lehmann in 1928.[14] Experts Allen Christenson, Néstor Quiroa, Rosa Helena Chinchilla Mazariegos, John Woodruff, and Carlos López all consider the Newberry volume to be Ximénez's ane and just "original."

Father Ximénez'south source [edit]

Father Ximénez'due south manuscript contains the oldest known text of Popol Vuh. Information technology is by and large written in parallel Kʼicheʼ and Spanish every bit in the front end and rear of the first page pictured hither.

It is generally believed that Ximénez borrowed a phonetic manuscript from a parishioner for his source, although Néstor Quiroa points out that "such a manuscript has never been found, and thus Ximenez'due south work represents the just source for scholarly studies."[15] This certificate would have been a phonetic rendering of an oral recitation performed in or around Santa Cruz del Quiché before long following Pedro de Alvarado's 1524 conquest. By comparing the genealogy at the end of Popol Vuh with dated colonial records, Adrián Recinos and Dennis Tedlock suggest a date betwixt 1554 and 1558.[16] But to the extent that the text speaks of a "written" document, Woodruff cautions that "critics announced to have taken the text of the first folio recto also much at face value in drawing conclusions nearly Popol Vuh'southward survival."[17] If in that location was an early post-conquest document, one theory (first proposed past Rudolf Schuller) ascribes the phonetic authorship to Diego Reynoso, one of the signatories of the Título de Totonicapán.[eighteen] Some other possible author could take been Don Cristóbal Velasco, who, also in Titulo de Totonicapán, is listed as "Nim Chokoh Cavec" ('Bang-up Steward of the Kaweq').[19] [20] In either case, the colonial presence is clear in Popol Vuh's preamble: "This we shall write now nether the Law of God and Christianity; we shall bring information technology to light because now the Popol Vuh, every bit it is called, cannot exist seen whatever more than, in which was conspicuously seen the coming from the other side of the sea and the narration of our obscurity, and our life was clearly seen."[21] Accordingly, the need to "preserve" the content presupposes an imminent disappearance of the content, and therefore, Edmonson theorized a pre-conquest glyphic codex. No evidence of such a codex has even so been found.

A minority, however, disputes the existence of pre-Ximénez texts on the same basis that is used to argue their existence. Both positions are based on two statements by Ximénez. The first of these comes from Historia de la provincia where Ximénez writes that he establish diverse texts during his curacy of Santo Tomás Chichicastenango that were guarded with such secrecy "that not even a trace of it was revealed amidst the elderberry ministers" although "almost all of them have it memorized."[22] The second passage used to argue pre-Ximénez texts comes from Ximénez'southward addendum to Popol Vuh. In that location he states that many of the natives' practices can be "seen in a volume that they have, something like a prophecy, from the beginning of their [pre-Christian] days, where they have all the months and signs respective to each day, one of which I have in my possession."[23] Scherzer explains in a footnote that what Ximénez is referencing "is simply a secret calendar" and that he himself had "found this rustic calendar previously in various indigenous towns in the Guatemalan highlands" during his travels with Wagner.[24] This presents a contradiction because the item which Ximénez has in his possession is non Popol Vuh, and a advisedly guarded item is non likely to accept been easily available to Ximénez. Apart from this, Woodruff surmises that because "Ximenez never discloses his source, instead inviting readers to infer what they wish [. . .], it is plausible that there was no such alphabetic redaction amid the Indians. The unsaid culling is that he or another missionary made the first written text from an oral recitation."[25]

Story of Hunahpú and Xbalanqué [edit]

Tonsured Maize God and Spotted Hero Twin

Many versions of the fable of the Hero Twins Hunahpú and Xbalanqué circulated through the Mayan peoples[ commendation needed ], but the story that survives was preserved by the Dominican priest Francisco Ximénez[half-dozen] who translated the document betwixt 1700 and 1715.[26] Maya deities in the Postal service-Classic codices differ from the earlier versions described in the Early Archetype period. In Mayan mythology Hunahpú and Xbalanqué are the second pair of twins out of 3, preceded by Hun-Hunahpú and his brother Vucub-Hunahpú, and precursors to the third pair of twins, Hun Batz and Hun Chuen. In the Popol Vuh, the commencement set of twins, Hun-Hunahpú and Vucub-Hanahpú were invited to the Mayan Underworld, Xibalba, to play a ballgame with the Xibalban lords. In the Underworld the twins faced many trials filled with trickery; eventually they fail and are put to expiry. The Hero Twins, Hunahpú and Xbalanqué, are magically conceived after the decease of their begetter, Hun-Hunahpú, and in time they return to Xibalba to avenge the deaths of their father and uncle by defeating the Lords of the Underworld.

Construction [edit]

Popol Vuh encompasses a range of subjects that includes creation, beginnings, history, and cosmology. There are no content divisions in the Newberry Library's holograph, just popular editions have adopted the organization imposed past Brasseur de Bourbourg in 1861 in social club to facilitate comparative studies.[27] Though some variation has been tested by Dennis Tedlock and Allen Christenson, editions typically accept the following course:

A family tree of gods and demigods.

Vertical lines point descent

Horizontal lines indicate siblings

Double lines indicate marriage

Preamble

- Introduction to the piece that introduces Xpiyacoc and Xmucane, the purpose for writing the Popol Vuh, and the measuring of the earth.[28]

Volume Ane

- Account of the creation of living beings. Animals were created first, followed by humans. The start humans were fabricated of earth and mud, only soaked up water and dissolved. The second humans were created from wood, only they were washed away in a flood.[29]

- Vucub-Caquix ascends.[29]

Volume Two

- The Hero Twins programme to kill Vucub-Caquix and his sons, Zipacna and Cabracan.[29]

- They succeed, "restoring order and rest to the earth."[29]

Book 3

- The begetter and uncle of The Hero Twins, Hun Hunahpu and Vucub Hunahpu, sons of Xmucane and Xpiacoc, are murdered at a ball game in Xibalba.[29]

- Hun Hunahpu's head is placed in a calabash tree, where information technology spits in the mitt of Xquiq, impregnating her.[29]

- She leaves the underworld to be with her mother-in-police force, Xmucane.[29]

- Her sons then challenge the Lords who killed their father and uncle, succeeding and becoming the sun and the moon.[29]

Volume Four

- Humans are successfully created from maize.[29]

- The gods requite them morality in order to keep them loyal.[29]

- Afterwards, they give the humans wives to make them content.[29]

- This book also describes the movement of the Kʼicheʼ and includes the introduction of Gucumatz.[29]

Excerpts [edit]

A visual comparison of two sections of the Popol Vuh are presented below and include the original Kʼiche, literal English language translation, and modern English translation equally shown by Allen Christenson.[30] [31] [32]

"Preamble" [edit]

| Original Kʼiche | Literal English Translation | Modern English Translation |

|---|---|---|

AREʼ U XEʼ OJER TZIJ,

Xchiqatikibʼaʼ wi ojer tzij, U tikaribʼal, U xeʼnabʼal puch, Ronojel xbʼan pa

| THIS ITS ROOT Aboriginal WORD,

Nosotros shall constitute ancient give-and-take, Its planting, Its root-offset besides, Everything washed in

| THIS IS THE Kickoff OF THE Ancient TRADITIONS

Nosotros shall begin to tell the ancient stories of the beginning, the origin of all that was done in

|

"The Primordial World" [edit]

| Original Kʼiche | Literal English Translation | Modern English language Translation |

|---|---|---|

| AREʼ U TZIJOXIK Waʼe. Kʼa katzʼininoq, Katzʼinonik, Kʼa kalolinik, | THIS ITS ACCOUNT These things. Still be it silent, Information technology is silent, Nevertheless it is hushed, | THIS IS THE Business relationship of when all is nonetheless silent All is silent Hushed |

Modern history [edit]

Modern editions [edit]

Since Brasseur's and Scherzer'southward first editions, the Popol Vuh has been translated into many other languages besides its original Kʼicheʼ.[37] The Spanish edition by Adrián Recinos is still a major reference, every bit is Recino's English language translation by Delia Goetz. Other English translations[38] include those of Victor Montejo,[39] Munro Edmonson (1985), and Dennis Tedlock (1985, 1996).[40] Tedlock's version is notable considering information technology builds on commentary and interpretation past a mod Kʼicheʼ daykeeper, Andrés Xiloj. Augustín Estrada Monroy published a facsimile edition in the 1970s and Ohio State University has a digital version and transcription online. Modern translations and transcriptions of the Kʼicheʼ text have been published by, among others, Sam Colop (1999) and Allen J. Christenson (2004). In 2018, The New York Times named Michael Bazzett'south new translation as i of the x best books of poetry of 2018.[41] The tale of Hunahpu and Xbalanque has also been rendered as an hour-long animated motion-picture show past Patricia Amlin.[42] [43]

Gimmicky culture [edit]

The Popol Vuh continues to be an important part in the belief arrangement of many Kʼicheʼ.[ citation needed ] Although Catholicism is mostly seen every bit the dominant religion, some believe that many natives practice a syncretic blend of Christian and ethnic beliefs. Some stories from the Popol Vuh continued to be told by modern Maya equally folk legends; some stories recorded by anthropologists in the 20th century may preserve portions of the aboriginal tales in greater item than the Ximénez manuscript.[ commendation needed ] On August 22, 2012, the Popol Vuh was declared intangible cultural heritage of Guatemala past the Guatemalan Ministry of Culture.[44]

Reflections in Western civilization [edit]

Since its rediscovery by Europeans in the nineteenth century, the Popol Vuh has attracted the attention of many creators of cultural works.

Mexican muralist Diego Rivera produced a series of watercolors in 1931 as illustrations for the book.

In 1934, the early on avant-garde Franco-American composer Edgard Varèse wrote his Ecuatorial, a setting of words from the Popol Vuh for bass soloist and diverse instruments.

The planet of Camazotz in Madeleine L'Engle'southward A Wrinkle in Time (1962) is named for the bat-god of the hero-twins story.

In 1969 in Munich, Germany, keyboardist Florian Fricke—at the time ensconced in Mayan myth—formed a band named Popol Vuh with synth player Frank Fiedler and percussionist Holger Trulzsch. Their 1970 debut album, Affenstunde, reflected this spiritual connection. Another band by the aforementioned proper name, this one of Norwegian descent, formed effectually the same fourth dimension, its name also inspired past the Kʼicheʼ writings.

The text was used by German flick managing director Werner Herzog as extensive narration for the start chapter of his movie Fata Morgana (1971). Herzog and Florian Fricke were life long collaborators and friends.

The Argentinian composer Alberto Ginastera began writing his symphonic work Popol Vuh in 1975, but neglected to complete the piece before his decease in 1983.

The myths and legends included in Louis Fifty'Flirtation's novel The Haunted Mesa (1987) are largely based on the Popol Vuh.

The Popol Vuh is referenced throughout Robert Rodriguez's boob tube show From Dusk till Dawn: The Serial (2014). In item, the show'south protagonists, the Gecko Brothers, Seth and Richie, are referred to as the embodiment of Hunahpú and Xbalanqué, the hero twins, from the Popol Vuh.

Antecedents in Maya iconography [edit]

Gimmicky archaeologists (first of all Michael D. Coe) have found depictions of characters and episodes from Popol Vuh on Mayan ceramics and other art objects (east.g., the Hero Twins, Howler Monkey Gods, the shooting of Vucub-Caquix and, equally many believe, the restoration of the Twins' dead father, Hun Hunahpu).[45] The accompanying sections of hieroglyphical text could thus, theoretically, relate to passages from the Popol Vuh. Richard D. Hansen found a stucco frieze depicting two floating figures that might exist the Hero Twins[46] [47] [48] [49] at the site of El Mirador.[50]

Following the Twin Hero narrative, mankind is fashioned from white and yellow corn, demonstrating the crop's transcendent importance in Maya culture. To the Maya of the Archetype period, Hun Hunahpu may have represented the maize god. Although in the Popol Vuh his severed head is unequivocally stated to have become a calabash, some scholars believe the calabash to exist interchangeable with a cacao pod or an ear of corn. In this line, decapitation and sacrifice correspond to harvesting corn and the sacrifices accompanying planting and harvesting.[51] Planting and harvesting as well chronicle to Maya astronomy and calendar, since the cycles of the moon and sun determined the crop seasons.[52]

Notable Editions [edit]

- 1857. Scherzer, Carl, ed. (1857). Las historias del origen de los indios de esta provincia de Guatemala. Vienna: Carlos Gerold e hijo.

- 1861. Brasseur de Bourbourg; Charles Étienne (eds.). Popol vuh. Le livre sacré et les mythes de l'antiquité américaine, avec les livres héroïques et historiques des Quichés. Paris: Bertrand.

- 1944. Popol Vuh: das heilige Buch der Quiché-Indianer von Republic of guatemala, nach einer wiedergefundenen alten Handschrift neu übers. und erlautert von Leonhard Schultze. Schultze Jena, Leonhard (trans.). Stuttgart, Germany: W. Kohlhammer. OCLC 2549190.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - 1947. Recinos, Adrián (ed.). Popol Vuh: las antiguas historias del Quiché. United mexican states: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

- 1950. Goetz, Delia; Morley, Sylvanus Griswold (eds.). Popol Vuh: The Sacred Book of the Ancient Quiché Maya Past Adrián Recinos (1st ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- 1971. Edmonson, Munro Due south. (ed.). The Book of Counsel: The Popol-Vuh of the Quiche Maya of Guatemala. Publ. no. 35. New Orleans: Middle American Research Institute, Tulane University. OCLC 658606.

- 1973. Estrada Monroy, Agustín (ed.). Popol Vuh: empiezan las historias del origen de los índios de esta provincia de Guatemala (Edición facsimilar ed.). Guatemala Metropolis: Editorial "José de Piñeda Ibarra". OCLC 1926769.

- 1985. Popol Vuh: the Definitive Edition of the Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life and the Glories of Gods and Kings, with commentary based on the aboriginal noesis of the modern Quiché Maya. Tedlock, Dennis (translator). New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN0-671-45241-Ten. OCLC 11467786.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - 1999. Colop, Sam, ed. (1999). Popol Wuj: versión poética Kʼicheʼ. Quetzaltenango; Guatemala City: Proyecto de Educación Maya Bilingüe Intercultural; Editorial Cholsamaj. ISBN99922-53-00-2. OCLC 43379466. (in 1000'iche')

- 2004. Popol Vuh: Literal Poetic Version: Translation and Transcription. Christenson, Allen J. (trans.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Printing. March 2007. ISBN978-0-8061-3841-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - 2007. Popol Vuh: The Sacred Book of the Maya. Christenson, Allen J. (trans.). Norman: Academy of Oklahoma Printing. 2007. ISBN978-0-8061-3839-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - 2007. Poopol Wuuj - Das heilige Buch des Rates der Grand´ichee´-Maya von Guatemala. Rohark, Jens (trans.). 2007. ISBN978-three-939665-32-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

- 2018. The Popol Vuh: A New Verse Translation. Bazzett, Michael (trans.). Seedbank Books. 2018. ISBN978-i-5713-1468-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

See also [edit]

- Ancient murals at El Mirador, Republic of guatemala

Notes [edit]

- ^ Modernistic Kʼicheʼ: Poopol Wuuj reads Mayan pronunciation: [ˈpʰoːpʰol ˈʋuːχ])

- ^ Hart, Thomas (2008). The Ancient Spirituality of the Modern Maya. UNM Press. ISBN978-0-8263-4350-5.

- ^ Christenson, Allen J. (2007). Popol vuh : the sacred volume of the Maya (Oklahoma ed.). Norman: Academy of Oklahoma Printing. pp. 26–31. ISBN978-0-8061-3839-viii . Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ Junajpu and Xbʼalanke in Modernistic Kʼicheʼ spelling

- ^ Christenson, Allen J. (2007). Popol Vuh: the sacred book of the Maya (Oklahoma ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 64. ISBN978-0-8061-3839-8 . Retrieved 3 Nov 2017.

- ^ a b c "Popol Vuh AHA". world wide web.historians.org. American Historical Clan. Retrieved three Nov 2017.

- ^ "Popol Vuh - The Sacred Book of The Mayas". www.vopus.org. VOPUS. Retrieved iii November 2017.

- ^ According to Allen Christenson, the mat was a mutual Maya metaphor for kingship (such equally "throne" in English) and national unity.

- ^ Christenson, Allen J. (2007). Popol Vuh : the sacred volume of the Maya (Oklahoma ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 21. ISBN978-0-8061-3839-8 . Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^ Ximénez's championship page reads in part, "cvra doctrinero por el real patronato del pveblo de Sto. Tomas Chvila" ('doctrinal priest of the district of Santo Tomás Chuilá').

- ^ Woodruff 2009

- ^ Scherzer also published a detailed inventory of the contents in an 1857 edition that coincides with the Ayer ms. Scherzer'southward copyscript and edition beginning at the third internal title: 1) Arte de las tres lengvas Kakchiqvel, Qvíche y Zvtvhil, 2) Tratado segvndo de todo lo qve deve saber vn mínístro para la buena admínístraçíon de estos natvrales, 3) Empiezan las historias del origen de los indíos de esta provinçia de Gvatemala, four) Escolíos a las hístorías de el orígen de los indios [annotation: spelling is that of Ximénez, simply capitalization is modified here for stylistic reasons].

- ^ Woodruff 2009 pp. 46–47. Brasseur mentions Ximénez's Popol Vuh manuscript in iii different works from 1857–1871, but never cites the library document every bit the source of his 1861 French edition. See Histoire des nations civilisées du Mexique et de fifty'Amérique-Centrale (1857), Popol vuh. Le livre sacré (1861), and Bibliothèque Mexico-Guatémalienne (1871). Information technology was non until fifteen years after his return to Europe that Brasseur suggested a specific provenance of his source material; he said that it had come from Ignacio Coloche in Rabinal. The inconsistency among his statements led Munro Edmonson (1971) to postulate that there had been multiple manuscripts in Guatemala.

- ^ Edmonson 1971 p. viii; Lopez 2007

- ^ Quiroa, "Ideology" 282)

- ^ Recinos xxx–31 (1947); Goetz 22–23 (1950); Tedlock 56 (1996)

- ^ Woodruff, "Ma(r)rex Popol Vuh" 104

- ^ Recinos 34; Goetz 27; see also Akkeren 2003 and Tedlock 1996.

- ^ Christenson 2004

- ^ After the list of rulers, the narrative recounts that the three Great Stewards of the main ruling Kʼicheʼ lineages were "the mothers of the discussion, and the fathers of the give-and-take"; and the "discussion" has been interpreted by some to hateful the Popol Vuh itself.[ commendation needed ] Since a prominent place is given to the Kaweq lineage at the end of Popol Vuh, the author / scribe / narrator / storyteller may have belonged to this lineage as opposed to another Kʼicheʼ lineage.

- ^ Goetz 79–80

- ^ "y así determiné el trasuntar de verbo ad verbum todas sus historias como las traduje en nuestra lengua castellana de la lengua quiché, en que las hallé escritas desde el tiempo de la conquista, que entonces (como allí dicen), las redujeron de su modo de escribir al nuestro; pero fue con todo sigilo que conservó entre ellos con tanto secreto, que ni memoria se hacía entre los ministros antiguos de tal cosa, e indagando yo aqueste punto, estando en el curato de Santo Tomás Chichicastenango, hallé que era la doctrina que primero mamaban con la leche y que todos ellos casi lo tienen de memoria y descubrí que de aquestos libros tenían muchos entre sí [...]" (Ximenez 1999 p. 73; English translation by WP contributor)

- ^ "Y esto lo ven en united nations libro que tienen como pronostico desde el tiempo de su gentilidad, donde tienen todos los meses y signos correspondientes á cada dia, que uno de ellos tengo en mi poder" (Scherzer 1857; English translation by WP contributor). This passage is found in Escolios a las historias as appearing on p. 160 of Scherzer'south edition.

- ^ "El libro que el padre Ximenez menciona, no es mas que una formula cabalistica, segun la cual los adivinos engañadores pretendían pronosticar y explicar ciertos eventos. Yo encontré este calendario gentilico ya en diversos pueblos de indios en los altos de Guatemala."

- ^ Woodruff 104

- ^ "Popol Vuh Newberry". world wide web.newberry.org. The Newberry. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^ Recinos explains: "The original manuscript is not divided into parts or chapters; the text runs without pause from the beginning until the terminate. In this translation I have followed the Brasseur de Bourbourg division into iv parts, and each role into chapters, because the organisation seems logical and conforms to the meaning and subject matter of the piece of work. Since the version of the French Abbe is the best known, this volition facilitate the piece of work of those readers who may wish to make a comparative study of the various translations of the Popol Vuh" (Goetz 14; Recinos 11–12; Brasseur, Popol Vuh, fifteen)

- ^ Christenson, Allen J. (2007). Popol Vuh : The Sacred Volume of the Maya. Norman, OK: Academy of Oklahoma Printing. pp. 59–66. ISBN978-0-8061-3839-viii . Retrieved xix October 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f thousand h i j m l "Popol Vuh". Globe History Encyclopedia . Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d due east Christenson, Allen J. "POPOL VUH: LITERAL TRANSLATION" (PDF). Mesoweb Publications. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- ^ Christenson's edition is considered the most up-to-date version of the Popol Vuh.

- ^ Christenson, Allen J. (2007). Popol vuh : the sacred book of the Maya (Oklahoma ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Printing. p. 59. ISBN978-0-8061-3839-8 . Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^ a b Bold and capitalized letters are taken directly from the source material.

- ^ Christenson, Allen J. (2007). Popol Vuh : The Sacred Book of the Maya. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 59. ISBN978-0-8061-3839-8 . Retrieved 19 Oct 2017.

- ^ a b Text has been broken in logical places to parallel the poetic construction of the original text.

- ^ Christenson, Allen J. (2007). Popol Vuh : The Sacred Book of the Maya. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Printing. p. 67. ISBN978-0-8061-3839-8 . Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- ^ Schultze Jena 1944

- ^ Depression 1992

- ^ MultiCultural Review, Volume ix. GP Subscription Publications. 2000. p. 97. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- ^ Dennis Tedlock (2013). Popol Vuh: The Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life. eBookIt.com. ISBN978-1-4566-1303-7 . Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- ^ Orr, David (December 10, 2018). "The All-time Poetry of 2018". The New York Times.

- ^ Amlin, Patricia (2004). Popol vuh. OCLC 56772917.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Automobile: "The Popol Vuh". YouTube . Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ Publinews (25 August 2012). "Popol Vuh es declarado Patrimonio Cultural Intangible".

- ^ Chinchilla Mazariegos 2003

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-12-13. Retrieved 2007-11-30 .

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Video News". cnn.com. October xiv, 2009.

- ^ "Video News". cnn.com. November 11, 2009.

- ^ "Breaking News, Latest News and Videos". cnn.com.

- ^ "El Mirador, the Lost Urban center of the Maya".

- ^ Heather Irene McKillop, The Aboriginal Maya: New Perspectives (London: West.Westward. Norton & Co., 2006), 214.

- ^ McKillop, 214.

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Popol Vuh. |

- Popol Wuj Archives, sponsored by the Section of Spanish and Portuguese at The Ohio Land University, Columbus, Ohio, and the Center for Latin American Studies at OSU.

- A facsimile of the earliest preserved manuscript, in Quiché and Spanish, hosted at The Ohio State University Libraries. Learn more about this project by reading "Decolonial Data Practices: Repatriating and Stewarding the Popol Vuh Online."

- de los Monteros, Pamela Espinosa (2019-10-25). "Decolonial Information Practices: Repatriating and Stewarding the Popol Vuh Online". Preservation, Digital Technology & Civilization. 48 (3–4): 107–119. doi:10.1515/pdtc-2019-0009. ISSN 2195-2965.

- The original Quiché text with line-past-line English language translation Allen J. Christenson edition

- An English translation past Allen J. Christenson.

- Text in English404 De pagina is niet gevonden Goetz-Morley translation subsequently Recinos

- A link to sections of the animated delineation by Patricia Amlin.

- Creation (1931). From the Collections at the Library of Congress

williamsshave1981.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Popol_Vuh

0 Response to "Popul Vohsomeone Has Once Again Began to Play Over Our Heads"

Post a Comment